Art Gallery Shows to See in January

This week in Newly Reviewed, Will Heinrich covers Jana Euler’s delightful absurdity, Lotty Rosenfeld’s portraits of the Pinochet dictatorship and Erich Heckel’s eerie dream world.

Chelsea

Jana Euler

Through Jan. 10. Greene Naftali, 508 West 26th Street; 212-463-7770; greenenaftaligallery.com.

I confess that I almost dismissed Jana Euler’s show “The center does not fold” because of “Where the energy comes from, connected,” a 9-foot painting of a white electrical outlet. I mistook it for the sort of clever, empty effort that fills so many hip corners of contemporary painting.

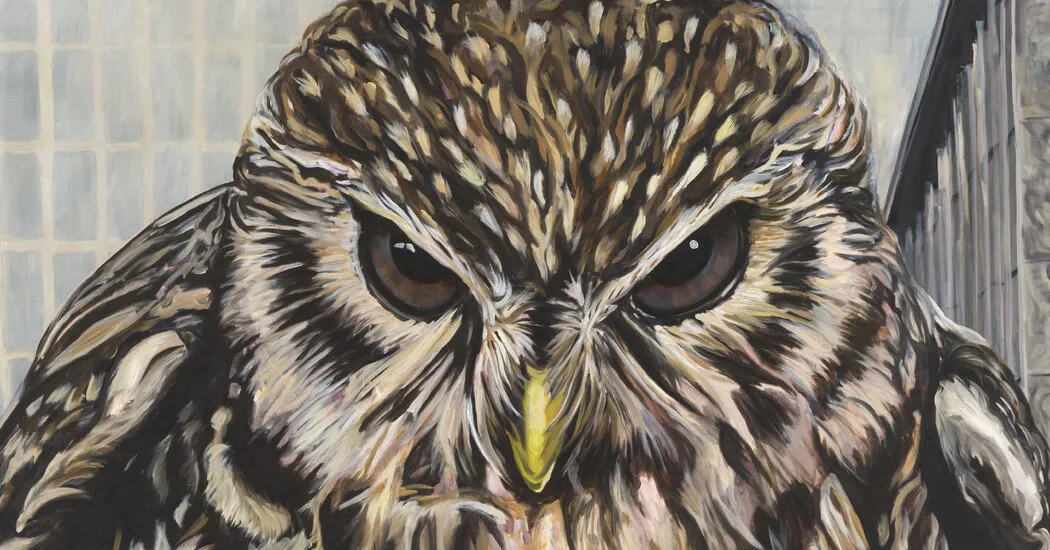

But as I continued into the gallery, an enormous owl, hunched over as if roller skating down an empty city street, made me laugh with delight. Elsewhere, a Frankenstein of dog breeds was striding upright through a crosswalk, and two pastel-colored “morecorns” — stoner unicorns with extra horns — were mating languidly on a desert highway.

There’s something absurd about a painter confronting the onrushing tide of smartphone photography, capitalist zeros and artificial-intelligence slop that define our present moment. What chance does Euler stand of saying anything meaningful against such a background, let alone of commenting meaningfully on the background itself?

By incorporating that very absurdity into her work, though, she enters the grand tradition of all the other self-aware, self-consciousness that painting as a medium has accumulated over the last 500 years, turning the problem around. Suddenly, current events, however threatening, are just more material to think about and make pictures of.

So I returned to the outlet. The contact openings evoked a face, or maybe an emoji, gasping in dismay, and once I noticed that, I couldn’t help wondering about the cord. But I also wondered whether the whole thing wasn’t just an excuse to make a hard-edge almost-monochrome, in which cloudy spots of brownish gray float behind a buttery sheen of white — a feint against the absurdity to create a pocket of safety for pure painting.

Harlem

Lotty Rosenfeld

Through March 15. Wallach Art Gallery, Lenfest Center for the Arts, Columbia University, 615 West 129th Street; 212-854-6800, wallach.columbia.edu.

Though billed as the first American retrospective for the feminist Chilean artist and activist Lotty Rosenfeld (1943-2020), “Disobedient Spaces” at Wallach Art Gallery is more tantalizing than comprehensive. But its handful of works on paper, and its broader selection of video art and documentation of Rosenfeld’s public actions, probe a problem as important for Americans now as for artists who, like Rosenfeld, worked under the Pinochet dictatorship: Is it even possible to talk to the other side?

Two works in particular are unforgettable. In “One thousand crosses on the pavement,” staged multiple times in the 1970s and ’80s, Rosenfeld used lengths of white ribbon to transform the white lines running down a highway in Santiago, Chile, into cross after cross after cross. These crosses could be memorials to the Pinochet regime’s victims.

But they’re also ingenious reminders that a single line changes subtraction to addition, or subversions of a system of regulation and control so ubiquitous that it’s almost always taken for granted. The action was legible as protest, in other words, but not dangerously so.

“El Padre Mio,” a searing 1985 video montage made with the writer and artist Diamela Eltit, is more direct. It combines footage of Pinochet giving a speech with the voice of an old man rambling incoherently, followed by a little girl telling a story about her father beating up her mother, scenes of protest, and so on. It’s a brilliant portrait of the disorienting violence of an authoritarian society, and it demonstrates that the fundamental disorder of such societies is as much psychological as it is political. The question is: If you didn’t already think Pinochet looked like a clown in his white military tunic and multicolored sash, would this be enough to convince you?

Upper East Side

Erich Heckel

Through Jan. 12. Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue; 212-628-6200, neuegalerie.org.

If Erich Heckel (1883-1970) isn’t as famous as the notoriously louche Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, with whom he and two others founded the influential Expressionist artists’ group Die Brücke (the bridge) in Dresden, Germany, in 1905, it may be because of his more orderly, less easily mythologized life.

Heckel’s paintings have all the wild color choices of a Kirchner; they give you the same sense of peering into an eerie, slightly sickly dream world where the people look like mannequins and the sunflowers writhe like people.

On the other hand, it may also be that Heckel’s paintings never quite achieve Kirchner’s manic intensity. At least, in this small but ample show of early work at the Neue Galerie, the thrills are in the prints. In a series of woodcuts of nude models, melting heads and ships at sea, Heckel orchestrates jagged marks with a fluid delicacy that creates a strangely mesmerizing tension.

“White Horses,” a colored woodblock print, contains just three figures in silhouettes, three tulip-like trees and two horses. But the composition, which features an upwardly angled road and squashed top edge, feels as crowded and dangerous as a battlefield. In “The Dead Woman,” the titular corpse lies in bed like a stage actress stiffly pretending to be dead, and in three prints of a young girl known as Fränzi, bold blocks of color are in such contrast with the figure that they almost burn your eyes.

See the December gallery shows here.