‘Cover-Up’ Review: Seymour Hersh, Scoops and Power

Halfway through the powerful documentary “Cover-Up,” the movie cuts to a gloomy image of the exterior of the White House. “Goddamn it, this story in The Times, the one by Hersh,” you hear President Richard M. Nixon say in voice-over. It’s 1973, the audio is from one of his secret White House recordings, and the thorn in his side is the indefatigable investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. “He doesn’t usually go with stuff that’s wrong,” Nixon says, before adding an inadvertent compliment that would please any decent reporter: “I mean, the son of a bitch is a son of a bitch, but he’s usually right, isn’t he?”

Over the years, others in power have voiced similar observations, as you learn in this portrait of Hersh, a towering figure in American journalism. Directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, it is an admiring, adamantly non-hagiographic look at a man and the worlds — of news-makers and news-breakers — that Hersh has traversed for more than six decades, including at different news outfits. (The Times that Nixon invoked is The New York Times.) That means that it’s also about the seductions and dangers of institutional power, especially as they play out in the relationship between American journalism and the government.

Poitras’s movies include “Citizenfour,” her acclaimed, Oscar-wining 2014 documentary about Edward Snowden, a former government contractor turned whistle-blower who released reams of U.S. surveillance data. Obenhaus, who has racked up some Emmy Awards, has produced nonfiction work for television and has worked with Hersh on earlier projects. Poitras first approached Hersh with the idea of making a documentary in 2005 (he declined). Hersh, who turned 88 this year, at last agreed to make the movie, and it began production in early 2023. He is an often wary, at times near-combative presence here, but he clearly trusts the filmmakers, who audibly engage with him from behind the camera.

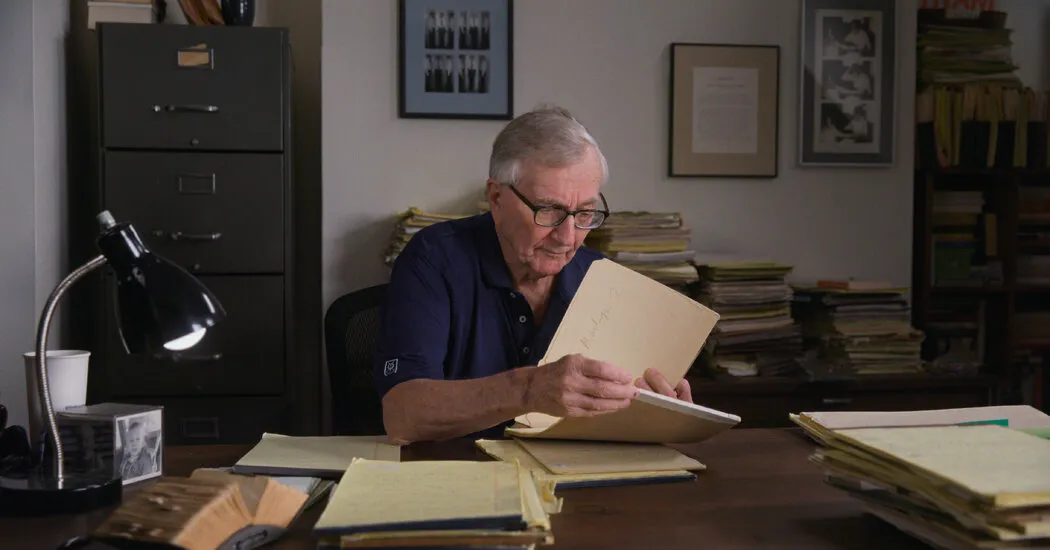

The sweep and magnitude of Hersh’s career can be gleaned from his office, with its stacks of papers, yellow notepads, overstuffed storage boxes, fat manila files and Rolodex cards scribbled with numbers for the likes of Daniel Ellsberg, the whistle-blower who helped expose America’s history of lies and deceit about the war in Vietnam. Hersh’s office serves as his shambolic redoubt — the filmmakers conducted a whopping 42 interviews with him for this movie — and it is an astonishing archival trove. These scraps of paper and labeled boxes are totems of his coverage of the major stories that he has chased and broken, from his first report on the My Lai massacre in Vietnam in 1969 to his news stories on Watergate in the 1970s and on the abuse of Iraqi prisoners by U.S. soldiers in Abu Ghraib decades later.

“Cover-Up” is a model of efficient, engaging documentary filmmaking; it looks good, for starters, and it moves energetically. For the most part, the filmmakers take a chronological approach to the narrative they tell and largely focus on Hersh’s professional life, bringing him into focus with a supple mix of archival and original material. David Obst, who got Hersh’s coverage of My Lai out through the Dispatch News Service, provides illuminating history, as does Bob Woodward. After Hersh, then at The Times, published his first Watergate story in January 1973, Woodward — who had been covering the scandal with Carl Bernstein for The Washington Post — called Hersh up. “Thank you,” Woodward said. “It’s lonely.”

The filmmakers open “Cover-Up” with an incident that Hersh wrote about in Ramparts magazine in 1969, and which makes a graphic case for investigative journalism as a check on — and bulwark against — government and military abuses. It’s a strong opener, and it plays like a mission statement for him and for Poitras and Obenhaus. On March 13, 1968, a military plane released a nerve agent during a covert open-air chemical test in Utah at the Army’s Dugway Proving Ground, the main weapons-testing center for America’s chemical and biological warfare. More than 6,000 sheep on nearby ranches died or had to be put down. The Army denied responsibility but its role was confirmed in a report released in 1997.

It’s an eerie prelude to a far more chilling horror: Three days after the sheep kill incident, a platoon of U.S. soldiers entered a Vietnam village, My Lai, and, using guns and bayonets, committed mass murder. By the end of the day, they had killed some 500 unarmed elderly men, women, children and babies. The Army covered it up. In the fall of 1969, Hersh, then a 32-year-old freelancer, received a tip from an attorney that an American soldier was to be court-martialed for a massacre. The tip led Hersh to Fort Benning, Ga., and in November his first My Lai news story sent shock waves around the globe. It opened with: “Lt. William L. Calley Jr., 26 years old, is a mild-mannered, boyish-looking Vietnam combat veteran with the nickname ‘Rusty.’” The second sentence described the criminal charges.

Hersh’s reporting on My Lai turned him into a public figure and earned him a Pulitzer Prize. He continued to break important stories, including at The Times, where in 1974 he exposed that, during the Nixon administration, the Central Intelligence Agency had violated its charter by illegally spying on thousands of American citizens, among other activities. He continued at The Times, not always happily, leaving it in 1979, and began focusing on investigative books. At that point, his legacy and the documentary grow more complex. While he was writing “The Dark Side of Camelot,” his 1997 book on John F. Kennedy, Hersh fell for a hoax that involved forged documents pertaining to Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe.

Hersh didn’t publish the documents, but the hoax became embarrassing, reputation-shaking news. The movie goes into the document debacle with Hersh, as well as his use of single sources, which has been frequently criticized. His blunt acknowledgment of his mistake in falling for the hoax as well as other troubling errors in judgment only humanizes him further. Hersh remains committed to his way of sourcing stories, just as he remains committed to sounding the alarm. Hersh is a tough, interesting cat, and this movie, by giving him his due and by addressing his failings, doesn’t simply tell the story of an individual but also of journalism.

Cover-Up

Rated R for disturbing atrocity images. Running time: 1 hour 57 minutes. In select theaters and available on Netflix on Dec. 26.